I’ve never been sure why “candy alley” in Kawagoe, in Saitama prefecture just outside Tokyo, is named as such—there aren’t an overwhelming number of candy sellers there.

None of the candy sold seems to be unique to Kawagoe, either. And that’s precisely the reason one particular bag of sweets jumped out at me this morning as I walked through Kashiya Yokocho, around the mid-way point of my Kawagoe day trip from Tokyo.

No Great Fire

Hard candies colored pink, green, purple and yellow, with delicate flower images inlaid in white, these were precisely what had given me the last burst of energy I needed to completed my Koyasan hike last May. I’d bought them on a whim, when my friend Suguru and I stopped at a tea house that would’ve been forgettable had it not been the only one around for miles.

Walking back toward Kawagoe’s Warehouse District, which is said to be Japan’s largest remaining collection of Edo-area structures, I recalled how Suguru had pulled out of our planned meeting the last time I was in Tokyo (in July), and how neither of us had so much as mentioned re-scheduling it since.

In particular, the Toki no Kane bell tower of the Kurazukuri Zone evokes pre-Tokyo Tokyo, having been originally constructed in the early 1600s. The operative word being “originally”—like most the rest of Kawagoe, it was destroyed in an 1893 fire, and rebuilt more than two decades after the Meiji Restoration, by which time the Tokugawa Shogunte that built it was little more than a memory.

As my footsteps began to fall within the shadow of the tower, I considered the similarity between Suguru, as I had restored his likeness in my mind after seeing the candy we shared, and the faithful reproductions all around me. No great fire had broken out between us—we hadn’t needed destruction to move on and re-build.

Synthesis and Simulation

The taste of the purple sweet potato soft cream I’d downed before saying sayonara to Kawagoe seemed to linger on my breath as the train pulled into Ikebukuro Station, though I hadn’t thought about the experience of eating it for even a second since I discarded the paper the cone was wrapped in.

Simulation, I thought to myself as I walked the “Visitor Route” through new Toyosu Market, which was purpose-built to replace the one at Tsukiji, is certainly preferable to synthesis. I wondered how long it would be until this place developed character, let alone of the sort that drips from its (deservedly) more famous cousin across Tokyo Bay.

But then, I arrived at a place where these two concepts—synthesis and simulation—become one. In the mind, the placard in front of the entrance read, the boundaries between different thoughts are ambiguous, causing them to influence and sometimes intermingle with each other.

I wondered if the art inside Tokyo’s much-ballyhooed teamLab Borderless digital art museum would react to the intermingling thoughts inside my head, memories of my Kawagoe day trip and the ones it, in turn, had dug up. (The cynical part of me wondered whether this art would be interactive at all.)

Digital Tea

Or indeed, if putting my own camera down would allow me to immerse myself in the art, if even for a second. The crowd itself was massive, certainly for a Monday in the middle of the Tokyo winter.

The fact that every person inside the museum seemed to have at least one camera or cellphone, and spent every other second posing (which is to say, pretending to immerse themselves in the art) made it seem impossible that I would have a chance to do so, momentarily or otherwise.

Still, I can’t deny that the exhibitions were beautiful, even if the concepts were something nebulous, and the near-dozen individual rooms began to blend together after I visited a few of them. On the other hand, it shocked me to think that some people spend all day here—I was ready to go before the second hour was up.

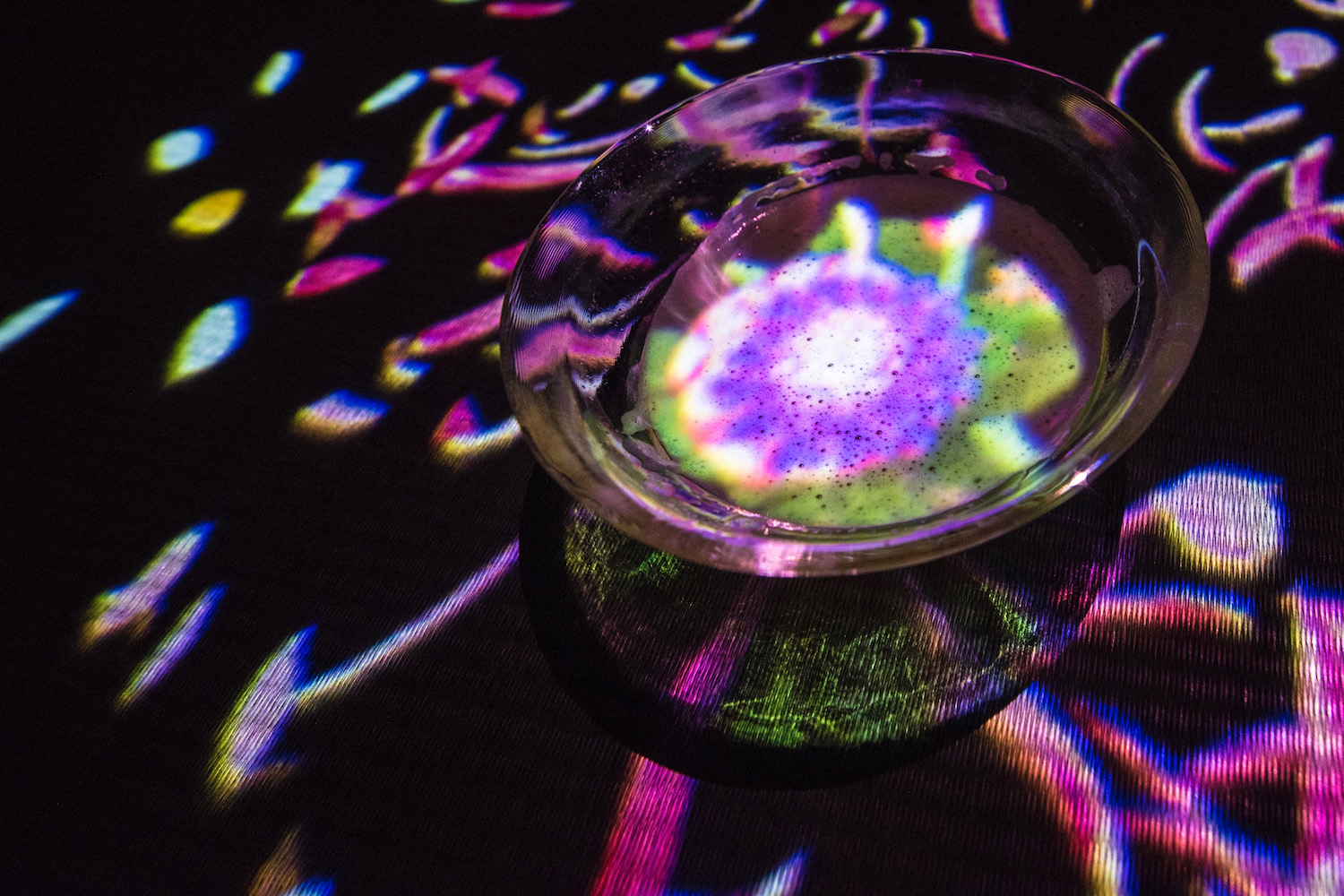

Which is not to deny that I’m as basic as the masses, at least not in some ways. I ended my visit to the museum, after all, they way most people in Instagram seemed to: With a cup of digital tea.

Like a Dandelion Blown

As I lifted up my yuzu cold brew tea, which was served in a mug intended for a hot drink, the flower projected onto its frothy surface began to break apart and scatter, like a dandelion blown by a strong wind. Oddly, doing this seemed much more intuitive than my lunch (Tenzaru soba, a local classic of matcha-infused buckwheat noodles served with tempura that many a tourist envoy on their Kawagoe day trip) had.

I’d forgotten what you do with the excess broth they bring out after you’ve nearly finished your noodles—I had to Google the answer Kawagoe residents have known since at least the time of the Great Fire.

Other FAQ About Taking a Kawagoe Day Trip

Is Kawagoe worth visiting?

Kawagoe is an interesting destination, although I admit it’s not the most exciting day trip from Tokyo. While “Little Edo” provides interesting architecture and a compelling cultural experience, the historical area is rather small. Additionally, since trains to Kawagoe depart from Ikebukuro in Tokyo’s northwest, the journey to reach the city is longer than you might be imagining.

What is Kawagoe known for?

Kawagoe is primarily known for its historic architecture, which is reminiscent of what Tokyo looked like centuries ago, back when it was known as Edo. Since most of old Tokyo was destroying by World War II bombing, Kawagoe offers the best opportunity to get an authentic glimpse into what Edo might have been like.

Where is Little Edo?

Little Edo is the historic part of Kawagoe, and where most tourists to the city are bound. Note that it’s not extremely close to Kawagoe Station. Rather, you’ll either need to walk around 20 minutes, or take a bus in order to reach the Little Edo area. The rest of Kawagoe is quite modern, and indistinct from any other small city in Japan.