I’m not sure if it was the flute flourishes, the drum strikes or the way the paper lanterns glowed red against the lapis of the blue hour. But something about traipsing amid the yama and hoko floats strewn around central Kyoto in the evenings leading up to the Gion Matsuri festival re-awakened me. “Me,” meaning the version of my consciousness that exists when I’m in Japan.

I wrote about this in another essay: I believe that travel creates branches in our being, that some essence of ourselves remains in each location (including in our home), unable to accompany our bodies as they speed through the upper atmosphere at hundreds of miles per hour.

The lanterns and the musical instruments. The smooth roughness of a passerby’s kimono fabric as she pushed past me. The click-clack of geta sandals on the pavement. And the vague woody aroma that could as easily have been musty tatami from one of the storefronts opened for the first time in months as it could the cologne of some ojisan passing through the crowd.

Maybe the sum of these stimuli booted up a long-dormant version of my operating system. Or maybe they simply triggered a chemical reaction that began to break the spell of my jet lag.

But I was in Japan, as reductive as a declaration like that might seem, declared on a website like this one. There was no mistaking that.

A few mornings later, I was approaching the Yasaka Namba Shrine in Osaka. Which morning is unimportant—they’re indistinguishable from one another at this time of year. Every day, the sun rises sometime during the four-o’clock hour; by the time things start to open just after six, there’s a stickiness in the air you can be sure will coat your body until your next shower, and maybe the one after that.

Then there are the locusts, whose song was an especially primal scream on the morning I’m referencing. I have no way of knowing how many inhabited the trees above the entrance to the shrine, which is supposed to be a lion’s head but doesn’t look especially cat-like to me.

But I did feel that they were less than welcoming, their chant far more muscular than any Buddhists’ (never mind that this this is a Shinto shrine), their timbre like 32nd notes hammered onto a violin’s E string with a thousand pounds of force and zero trace of rosin.

I felt the same way at another shrine—Osaka Tenmangu, which the city’s annual Tenjin Matsuri honors, and also where it begins—even though the signage and the smiles of the volunteers and the vibrant scarlet of the kanji for ice (which invites all who pass to cool themselves off with kakigori) suggested precisely the opposite. Of course I was welcome—wasn’t everyone?

There was the chance, of course, that it was just me. Even if I hadn’t been exhausted from having attended the Yamaboko Junko parade of the aforementioned Gion Matsuri before leaving Kyoto, the sheer heat of the day would’ve zapped my judgment the same way it did my joie de vivre. The “Real Feel” was nearly 120ºF (which sounds less severe in Celsius, even though I generally try to use that scale where possible).

It all melted together, like the syrup and the condensed milk (and probably some dripped-in sweat, if we’re being honest) melt into the bottom of the kakigori cup right as soon as you’ve gotten the hang of eating it. Like all Japanese mornings in mid-to-late July. Like the majority of Shinto shrines—most are like Osaka Tenmangu; zero others I’ve been to resemble Yasaka Namba Jinja.

One second I was reading up on the monstrous statues stood before me, feeling as wilted as the desiccated fronds of sakaki stapled to the supports of the awning, itself draped in garlands of shells strung to resemble wisteria. The next I was back in Kyoto walking through the yoiyama with my dear friend Eriko, who’d been in the old capital not for the purpose of seeing me, but because she’d decided to take an incense making class.

“All the ingredients are imported,” she explained, when I asked her whether she thought she might’ve stumbled onto the new business opportunity she’s told me she’s wanted for more than a year now. “They don’t even use wood grown in Japan. So unless I use ingredients from the supermarket and am able to make people pay extraordinary prices for something ordinary, there’s no chance.”

Still another instant I was on Osaka’s Sakuranomiya Bridge, sauntering across with the intent of stopping the moment the fireworks began; I looked forward to playing dumb when the policeman who were there to keep foot traffic moving inevitably told me I couldn’t pause to take a photo, let alone a series of them taken on a self-timer to avoid vibration.

Then, in a moment of kismet, every other person seemed to have the same idea as me, rushing the bridge railing as if we were all at a rock concert. While the keisatsu (to their credit) did briefly try to disperse us, it quickly became clear that the scale of the task would be insurmountable. They gave up, without so much as an angry look toward any of us, at least not that I could hear.

As the explosions went off—I felt guilty for enjoying them, knowing how terrified they must’ve made all the dogs within a kilometer of the Ou River’s banks—I realized the moment was as much the result of dumb luck as it was careful plotting: I’d walked literally for hours during the lead-up to the boat procession, even as virtually all other revelers (certainly, those who’d stood for the better part of an hour south of the shrine gate waiting for the land procession to begin) laid on tarps on either side of the river, most of them without a view of anything but trees, in a vain attempt—tarp plastic conducts heat more than it repels it—to cool themselves off.

The brutal percussion of the fireworks, and how they drowned out the droning of the locusts no doubt holed up in the trees blocking most of the million people attending the festival from seeing anything of note—the pure shock of it might’ve killed the pests outright.

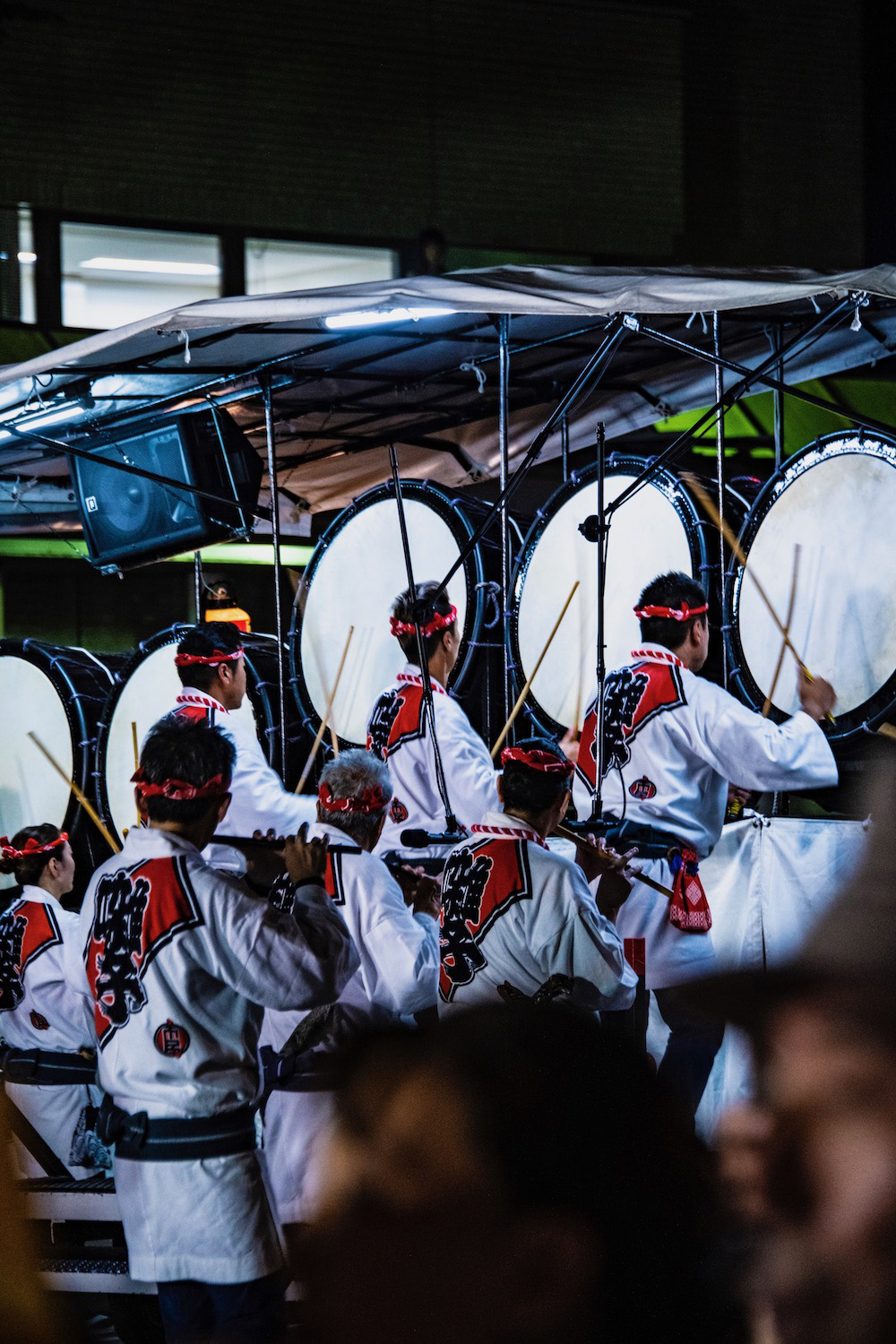

The actual percussion that had undergirded the land procession, serving as a metaphysical map for the towers the danjiri seem to be building as their move their hands upward with each beat, as if they’re on the cusp of reaching some precipice and, at once, damned to climbing the proverbial ladder for all eternity.

The softer syncopation that defined the speech of the Japanese-Russian couple that entered into a forgotten (but not forgettable) Nara shokudo with their biracial (and beautiful) son, their conversation too soft for me to ascertain which of their common languages they were speaking.

All these slices of my waking life seemed to exist simultaneously, though I can’t be sure whether I was astrally projecting or merely dehydrated.

When I was in Hiroshima in early April, I badly twisted my ankle while walking down an old stone staircase toward Miyajima’s Itsukushima Shrine. The injury eventually healed, but I’ve since developed something of a complex, never having seen myself as an especially clumsy person before that incident.

I tried to jettison any thoughts of it from my mind as I began the near vertical-climb at the start of the Nakahechi, the most popular portion of Wakayama prefecture’s Kumano Kodo pilgrimage.

Initially, I focused on my circumstances. The oppressive heat and humidity, which even under full shade just past 7 AM, were among the most oppressive I’d ever felt in Japan outside of Okinawa. The stupidity of my decision not to take the man at the trail entrance up on his offer to ship the second of my two backpacks to my accommodation ahead of me.

The generalized anxiety that, while not explicitly warned about the possibility of it happening, a bear—the kuma (熊) of the route’s name is the character that represents the beast—might cross my path.

Before I knew it, I had entered what I’ve come to think of as “monkey mode”—that point in a hike where you don’t even really have to think about anything, where you just move through nature automatically because…well, isn’t that what our ancestors did for millions of years? This was shortly before arriving in Takahara, the first notable stop along the trail, where many people stop for the night.

But not me—I was bound for Chikatsuyu; like Takahara from Takiji (the beginning of the trail), it was around 4 km away. Or at least that’s what I convinced myself, as I sipped a full-sugar Pepsi (I rarely drink these or soda of any kind, except when exerting myself in full sun) looking down on a chartreuse rice paddy beneath emerald, conifer-covered mountains.

Chikatsuyu, the signpost behind me read, raining immediately on my parade. 9.3 km.

Ordinarily, a distance like this wouldn’t have intimidated me. I’ve hiked to Everest Base Camp, after all; I’ve “climbed” Japan’s own Mt. Fuji (even though that’s more of a hike than a climb). Between the weather and the ~20 pounds of extra weight (in addition to my normal ~50 pound backpack), however, I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel a bit of dread as I tossed the soda can in a bin, and made my way once again under a canopy of sugi and hinoki.

While this ended up being harder than it might’ve in a different season or with less cargo, the reality was that I still completed the hike (13.3 km in total) in under five hours, an entire hour below the lower bound of how long Japanese authorities say it should take.

The sky opened up shortly after I arrived at my spartan minshuku; the town is small enough that its owner happened to be driving by and, upon seeing me hiding under an awning like a cat, allowed me to check in far earlier than I should’ve been able to do.

I began my second day’s hike—this time, 25 km from Chikatsuyu to Hongu, home of the largest and most important shrine along the entire route—feeling like my old hiking self again, not unlike my time amid the matsuri of Kyoto and Osaka had transported me back to the versions of me that I guess, in some universe, are perpetually roaming those cities’ streets.

Unfortunately for me (and for my old hiking self), I’d at some point abandoned the very good habit of focusing my internal thoughts on my immediate external circumstances, and had taken instead to listening to the ridiculous soliloquies of my internal monologue.

This was unfortunate not just because of how magnificent said external circumstances were—hydrangeas still in nearly perfect bloom atop the stone walls of a tiered cemetery; a shrine built amid cedars so massive I could just as well have been on Yakushima island—but because it caused me to make bad decisions.

The first was after a long descent through a warmer forest, where ferns and sacred sakaki trees had grown to cover the forest floor in the spaces were light shone down, despite the best efforts of the evergreens. I had misinterpreted the two-pointed “Kumano Kodo” marker as meaning to head down instead of up, even though in hindsight it was clear the downward path was not a trail. This detour only cost me about 10 minutes.

The second was longer and more severe—and, in my defense, happened in the context of an actual detour. Be that as it might have been, I stupidly walked along a highway for at least a half an hour. Even worse, the real re-routing was almost as vertical as the very first portion of the trail had been the day before; in spite of the fact that I’d been wise enough to forward my second bag before leaving Chikatsuyu that morning, it still tested my strength.

As I sat eating lunch at a shrine whose ground cover was so blue a green it looked fake, I tried not to fixate on my mistakes. The issue isn’t that you got lost, I reminded myself, but that you found yourself.

The rest of the afternoon, if I’m honest, was a blur. I arrived to Hosshimon-oji, unofficially the “second-to-last” shrine, and realized that Kumano Hongu Taisha was still a whopping 6.9 km away; by the time I reached that one, relief so overwhelmed all the other emotions I was feeling that I didn’t stick around long enough to truly appreciate it. I did make sure to treat myself to kakigori, however, which I enjoyed as I looked out on the world’s largest torii gate.

On day three, I wasn’t doing a “big” hike but rather two mini ones: The two-kilometer sprint up the Daimon-zaka slope to the Nachi Taisha waterfall temple; and the hundred or so stone steps that led to the Kamikura Shrine in the harbor city of Shingu.

What astonished me about both these hikes was the ease with which I completed them, in spite it being objectively much hotter and more humid near the sea than it had been in the mountains. At the latter, in fact, I literally sprinted up the side of one of the boulders the main shrine building is wedged between, with a tsuyo-sa that seemed to frighten the elderly Japanese women who watched me do it.

Although my entire body hurt from what I’d put it through over the preceding 48 hours, never once did I think about what happened in Hiroshima, let alone about the mistakes the schism between my inside and outside had caused the previous day.

I didn’t think at all actually—I just did it.

Arriving in the mountain town of Gujo Hachiman, which sits roughly halfway between the Seto Inland Sea and the central Japanese Alps, “fake” probably wouldn’t be the first word to come to your mind. From the dozens of fishermen waist-deep in the rapids of its rushing river, to the weathered lanterns strung above its main street, to the relative lack of foreign tourists you see, it appears to be the picture of authenticity.

The castle rising high above it all looks like a literal cherry on top. And yet this structure—the proudly-proclaimed oldest surviving reproduction of a Japanese castle—is the primary emblem of the town’s artificiality.

I’d made my way there circuitously, having spent half the previous day on a train (first, from Shingu to Nagoya and then from Nagoya onward to Takayama); although I had originally planned to go by bus, I ended up renting a car so that I could nest Gujo (as I’ve come to call it in my mind; I’ll go ahead and assume locals do) with a couple of other destinations.

I tried not to dwell as I strolled along Ogawa Lane, which like Tsuwano in the San’in region, is one of many places in Japan where drainage ditches are so clean large koi swim in them. Even here, however, I wondered how much of the story was true.

Maybe they filled the canal with spring water, I thought. Maybe the fish are someone’s pets. I thought back to an announcement on the second train from the day before when, upon passing through a locally famous onsen town, an automated voice announced the legend behind it (that a wounded crane, or maybe a stork, had miraculously flown again a day after unsuspectingly bathing its waters). How many times had I heard that one before?

The other option—and maybe the better option—was to lean into it. I was bound, after all, for the so-called “Sample Village,” which alongside a few other factories in Gujo is one of the primary centers of production for the plastic food samples you see in the windows of teishoku and shokudo restaurants all around Japan.

From there it was back in the car; I decided to take local roads, rather than paying a steep ¥3,600 toll to reach Gokayama the fast way. Drives in Japan tend to provide a lot of time for thinking. Speed limits are slow and locals always obey them; the few opportunities there are to overtake are usually difficult to execute.

It was a strange thing to continue fixating on, I admit, given how completely I’d invested myself in Japan over the previous decade. Was the country, to whose tourism fortunes I’d tied my own professional ones, actually as real as it—and I—claimed it to be? Or perhaps more accurately, is anyone actually even interested in the “real” parts of traveling in Japan, or do they just like it because it’s unfamiliar?

Gokayama’s Suganuma village, a seemingly more “authentic” version of the more famous Shirakawa-go, was fertile ground for continuing to ponder this.

On one hand, it did appear that people actually lived there; the museums, gift shops and cafes strewn about the dozen or so Gassho farmhouses seemed to supplement their existence, rather than justify it as was the case down the river. Notably, visiting this village is impossible without having your own vehicle or taking a private tour, which probably has something to do with the calm.

On the other hand, arriving at Shiroyama Observation Deck to look down on the tourist trap, the reality was that (at least from a bird’s eye perspective), fake Shirakawa-go was just so much more impressive than real Gokayama, and not just in terms of its much grander scale. I doubt it would’ve persisted (and certainly not grown) without all the tourism yen; the funds had clearly been reinvested many times over.

As I made the final sprint back toward Takayama just in time to return the car, most of it inside what has to be one of the longest tunnels in the world, I thought back on the rest of my trip—and all my trips. In my heart of hearts, could I really say that my favorite experiences were always the most genuine ones? Am I seeking out “real” experiences, or just the few remaining ones that are still unfamiliar to me?

Stopping for gas just outside of town, I entered into the adjacent 7-Eleven, where floral, earthy aromas overcame me as I lunged toward the energy drink section of the cooler. This particular konbini appeared to have partnered with a local farmer, as all manner of fresh produce crowded ramshackle shelves that had been thrown up in the area where bottled water overstock might be stacked in more urban stores. Eggplants, daikon, potatoes—oh my!

And peaches: So ripe and sickly-sweet than I could press deep into their flesh through the stiff plastic they were packed in. As a midi-muzak version of The Beach Boys’ “Kokomo” blared over the store’s speaker, I grabbed a box of them and headed toward the register to pay.

If Gujo Hachiman is a fake place that looked real, Nagano’s Kamikochi Valley is its subversion. Although the wintergreen waters that rollick across the smooth stones that have fallen down from towering Alpine peaks for eons are the picture of virgin nature, the sheer number of buses to here from all over Japan has turned the area into something of a city park.

Interestingly, a certain number of day visitors—the REI contingent, as I’ve come to call them—choose to walk the flat trails (which are so close to the station you can smell the exhaust) in full trekking regalia, with camping backpacks, heavy-duty hiking boots and buckets hat that, when combined with still-prevalent face masks, make their wearers practically anonymous.

I heard bear bells dangling—dozens, maybe hundreds—as if bears would hang out here, except to sweetly beg for scraps. They charge an entrance fee to visit one of the ponds, for god’s sake!

Later in Matsumoto (a city I love and have visited often over the years), I checked into a hotel that seemed straight out of a horror film. Or, more accurately, dropped me into one. It was at least a decade older than I was; the only thing filthier than the half-century of smoke farting up out of the carpet every time I stepped on it was the debris (which appeared to be fecal) that bubbled up out of the pipes when I attempted to drain the bathtub.

As I rushed through the city with my bags toward my new hotel—I made sure to select a brand-new one; none of my usual Matsumoto haunts had availability—I felt both like I was escaping imminent murder and that I had won the lottery. Going up to my third-floor room in the spacious, modern elevator, I watched myself on the CCTV feed above the buttons.

A horror movie, but with a happy ending.

Fujisan was teasing me over the horizon as I ascended the Komagatake Ropeway. Or at least that’s what I ascertained from the diagram just above the window which, apart from it, was blocked by all the bucket hats my fellow “climbers” were wearing.

I put the word in quotes because while this is what they fancied themselves—many probably saw themselves as mountaineers—I had a feeling that the trails of the so-called Senjojiki Cirque would be more akin to hiking than to climbing.

I climbed the makeshift stone stairs of the trail, to be sure, almost as if I was sprinting up them. I passed everyone so quickly I could hardly hear them popping off about my Nike sneakers or non-athletic clothing; even the violet broadleaf harebells blurred in my peripheral vision I was moving so fast, although I could see that some of them were smashed—clearly, not everyone had obeyed the request to stay behind the green rope.

The scenery certainly was alpine, more than anywhere else I’d seen in Japan. In fact, with the exception of this place—the Chuo Alps—and Kamikochi, I’ve often questioned whether calling the mountains of central Japan “Alps” at all is helpful, let alone accurate; my Swiss best friend thought I was kidding when I told her Japan was home to a range named as such.

In spite of how easy ascending the first two trails proved, I opted to turn around instead of completing a third. Not because I couldn’t have completed it—I’d have been to the top in a matter of minutes—but rather because I had somewhere else to be. I did linger for a moment, not so much to catch my breath (I never really lost it), but because I didn’t want any of the laggards I’d zipped past on my way up see me descend having obviously not made it all the way to the finish line.

As I turned around, the previously visible tip of Fuji had all but disappeared behind clouds that looked like they’d been whooshed out of a whipped cream container.

Because I did end up getting back down to Komagane Town a bit earlier than I’d anticipated, I opted (as I’d done on the way from Gujo to Gokayama) to take local roads to reach Hananomiyako Koen, a flower park not far from Lake Yamanako near the base of Fuji. If you’ve been to Japan you’ll realize this would be a great distance, even via the expressway.

Traversing it trapped between cars going less than the already modest speed limit—it took me nearly four hours to travel 160 km, or 100 miles—was nothing short of maddening. The fact that the mountain was still almost totally obscured behind the Reddi-Whip clouds when I parked my car zapped most of what was left of my sanity, never mind my creative motivation.

Yet upon entering the park, as I traipsed between two particularly tall rows of himawari, I turned around to see the mountain’s iconic silhouette visible almost completely, with the exception of a few fluffy clouds that were actually a nice accent, considering that the whole scene was backlit.

Bees buzzing around me as I manhandled the hanging sunflower gourds, I was mindful of my luck to have seen the mountain, albeit not fixated on it. When I later pulled out of the parking lot, however, and noticed it had become even more invisible than it was when I arrived, it was difficult not to feel a bit of kismet, not unlike the moment the fireworks had gone off as I stood, perfectly positioned, atop Osaka’s Sakuranomiya Bridge.

It was seven years ago next month that I first looked upon the nebuta floats that parade around Aomori’s streets every August. It was my first time to Aomori at all; I’d heard of the city but never imagined I would visit there. At that time, Japan was but one of many countries I enjoyed traveling to. The idea that I might one day focus on it seemed inconceivable.

Seven years, of course, is the amount of time it takes for every cell in your body to regenerate. Or at least that’s what people who are almost certainly unqualified to declare as much seem to love declaring with certainty.

It was just short of a year ago, to be sure, that I first visited Akita City (I’d previously been to the prefecture many times); it was my first trip back to Japan since the border reopened.

Although I was thrilled to have returned, I was coming off more than two years of bitterness: At Japan’s government, for having chosen race politics over science; and at myself, for having made the decision to throw all my eggs into the basket of a country that history suggested might be prone to such choices.

As had been the case in Aomori six years before than, I visited the hall that houses Akita’s own floats (they’re called kanto here, not to be confused with the Japanese region), which had been in storage for much of the prior three years, ostensibly on account of the pandemic. Unlike in Aomori, however, my visit here had been intentional.

And so was the intention my visit engendered: I was going to come back and see the Kanto Matsuri for myself the following August. Which also happened to be when the Nebuta Matsuri would be taking place.

In fact, you might say this intense burst of inspiration was the Big Bang that birthed this entire trip; I decided the earlier festivals in Kyoto and Osaka would be the kick-off; while I’d originally planned to climb Fuji (again) between the two matsuri pairs on either end of my two weeks, I obviously decided to split that week between the Japanese Alps and the Kii Peninsula.

You’d think, given how long a tail this seeming typical summer visit to Japan had, that I’d have been anxious attending the two-part grand finale—the parades in Aomori and Akita, respectively—wanting to capture both perfectly.

But a strange thing happened, somewhere between a particularly close lunge of one of the multi-faced nebuta toward where I was standing in Aomori, and marveling as a very young man held a massive kanto just feet from me, using only a single one of his hands.

I’m not sure whether it was because I’m weeks-deep into a trip, or because I’ve just been doing this so long that it’s second nature. But for the first time in a long time, it really felt like my camera was an extension of my body—no, of my consciousness. Capturing it was a function of experiencing it. Which may sound like a given but trust me, it’s not. (If you create content in any commercial capacity, you’ll viscerally understand that).

I’m also not sure whether it was under Aomori’s cotton candy skies, or the bluer, moodier ones that set in over Akita as its lanterns lit up, that I asked myself the question simply. Can I really live in this moment?

But it was definitely in Akita—the last night of this trip, when my Japan self began the slow process of powering down, only to awaken again the next time I touch down at Haneda or Narita—that I received the answer. It was visceral, and it was clear.

It float into my awareness as I was walking back to my hotel sweat-soaked, the yolk of the egg from my yakisoba still viscous on my lip, the trill of flutes a mile away flying over the chirping of the crosswalk in front of me. Yes, I answered myself, almost mockingly.

This was the summertime singularity I had so long ago dreamed up. Now, I’m ready for rebirth.